GIORGIO MORANDI & PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA:

REPOSE & ENERGY

By Dorothy Koppelman

In 1983 I looked at the prints and paintings of Giorgio Morandi, the quiet 20th century painter of humble still lifes and saw a relation to the grand frescoes of Piero della Francesca in the way Repose and Energy were crucial in the technique of both. I learned later that Morandi felt a deep kinship to Piero, a relation which has been noted by Roberto Longhi and other contemporary critics. —DK

I know that every painting of every year and place answers Yes to every aspect of Eli Siegel's Fifteen Questions, Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? We know, too, that study of these questions could make every person like the world more and can make people happy. I shall look tonight at the work of two artists, one fairly contemporary and one who worked more than 500 years ago; both men illustrate centrally Question 10 which Eli Siegel asks on Repose and Energy:

Is there in painting an effect which arises from the being together of repose and energy in the artist's mind? —can both repose and energy be seen in a painting's line and color, plane and volume, surface and depth, detail and composition? —and is the true effect of a good painting on the spectator one that makes at once for repose and intensity, serenity and stir?

Giorgio Morandi

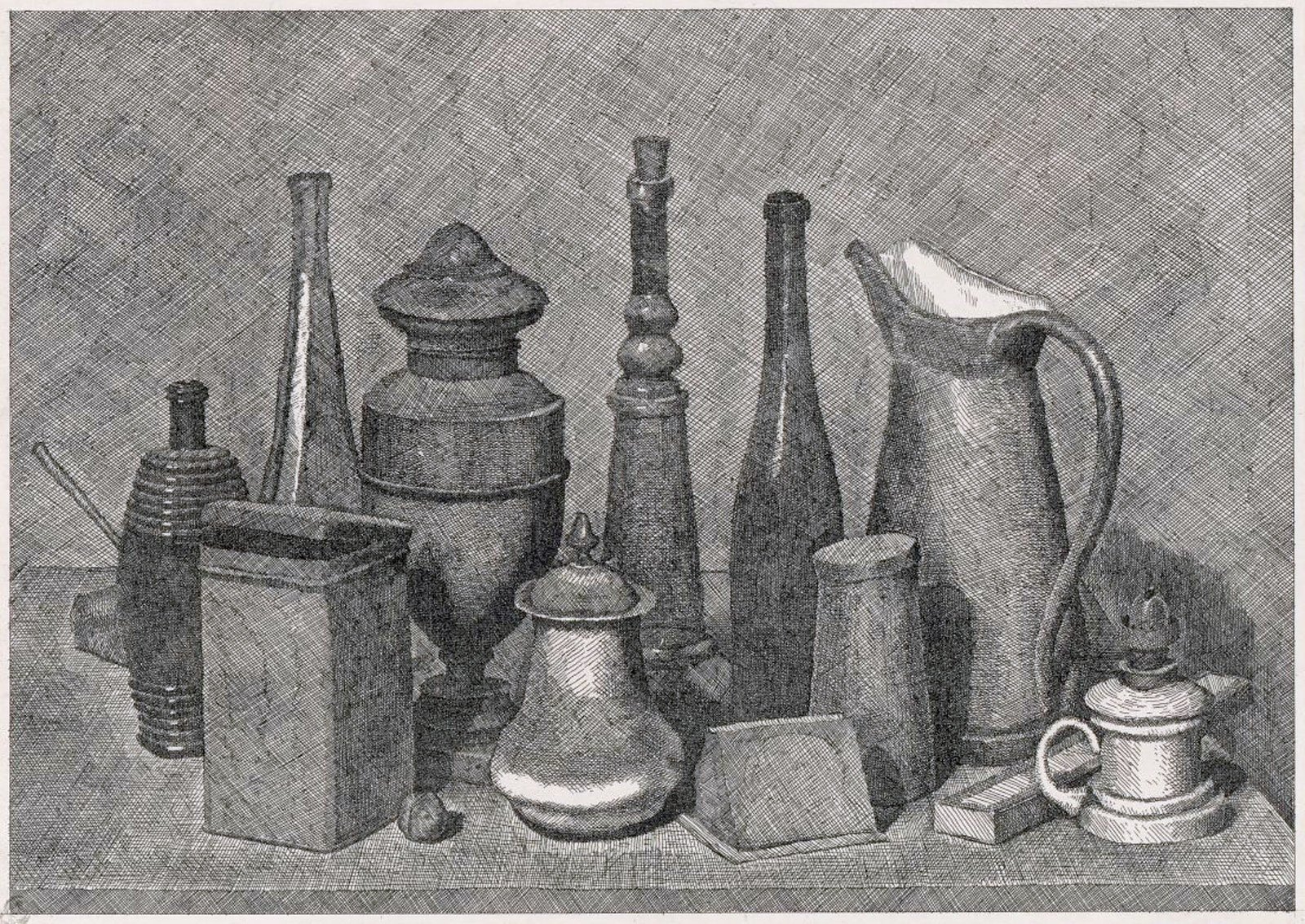

Let us look first at several still lifes by Giorgio Morandi—the name still-life—those two words still and life—are a oneness of repose and energy. And Giorgio Morandi, who lived until 1964, spent most of this century looking at, rearranging, studying, painting, and doing, etchings of his vases, bottles and jugs.

He did etchings on copper plates where, with small crosshatched lines he noted the way light and dark brought motion to quiet objects.

As he watched light move on surfaces, tracing curves and indentations, he seemed to understand the inner life of objects.

The contemporary painter Wayne Thiebaud, who so much admired and learned from Morandi, wrote that—

He gave an intimate view of his deepest thoughts. We watched him inquiring after the devilish questions of essences and substances.

Is this not a oneness of repose and energy in the artist's mind? And in this small work, only 13 7/8 inches wide by 9 and 7/8 inches high, repose and energy seem to take substantial form. The tall blue and white bottles stand like sentries. The deep blue bottle on the right is also translucent and the bottle on the left seems thickly and softly shrouded. But even as they are different and separate, their necks slightly incline towards one another. they are stiff outwardly, but they betray an inner motion. There is energy in contrast as all the bottles are pressed close in the center of the flat landscape, and yet we become slowly aware of a blue atmosphere which fills the space.

There is playful activity in the midst of those tall bottles; a pale yellow cube timidly appears in the center, and the handle of a brown jug asserts itself, comes center stage and becomes part of the waiting white bottle. And there is a soft blue, tall something in the background—a combination perhaps of essence and substance.

There is a quiet melody, a composition of deep blue notes and bright white highlights as these bottles touch and withdraw ever so slightly as they go their vertical way.

As Thiebaud observes:

Morandi suggests we are all single in this world, hoping for independent repose. But our best opportunity for a community of excellence depends upon a collection of enlightened individuals.

Here, round bowls snuggle just behind and next to slim-necked vases. Objects stay in place and their edges push against one another; they huddle in almost a protective line-up below the quiet, grey, and yet glowing space above. The thickness of the paint strokes, makes for a quivering separateness and togetherness within that rectangular, encompassing whole.

“Can both repose and energy be seen in a painting's line and color?” —asks Mr. Siegel. Color by its very nature is a oneness of repose and energy. All color asserts itself and recedes. It is light reflected from and absorbed by objects. Morandi's color puts energy and repose together through being so muted. It almost becomes substance as surface. And assertion and recession present themselves in the reposeful grays, pale yellows, and the bright white of that fluted vase so firmly sitting on the right.

When I was at the Guggenheim retrospective of Giorgio Morandi's work, I was peering closely at this etching when I suddenly became aware that I was in the midst of other people, all politely jostling one another. We were like the bottles, the same and different, heads tipped every which way, the edges of our clothes in motion as one stepped forward, another back, another hidden—peering over a shoulder. Yes, humanity is mirrored in these tall and short, thick and thin, shy and aggressive, graceful and awkward, narrow and wide, uncertain and purposeful, light and dark bottles. And all are related as the artist lovingly uses his needle to inscribe into that metal plate one object after another in strokes that are heavy and light, thin and thick, the same and different. There is a dance of relation here—rest, on-two-three, move, one-two, and it is this lovely junction of differences which can give us the proud emotion Eli Siegel describes: “calmness and intensity, serenity and stir,” at once.

Piero della Francesca

We are looking now at The Risen Christ, painted more than 500 years ago by Piero della Francesca, the artist said by some to have painted in Arezzo, Italy, "the most beautiful mural paintings in the world," and this, "the most beautiful painting.”

This is the morning when, after having been crucified, entombed, forsaken, guarded only by unseeing, unthinking soldiers, Christ, in the early morning, comes back to life. Every inch of this painting is an orchestrated oneness of energy and repose: it says that life is like that.

Energy is in the risen Christ. He is vertical, central, and he comes up from the ground, above the sleeping soldiers. But there is repose in the Christ figure too—in its soft, pale pinkish color, gently modeled forms, curving folds, and the straight gaze.

And there is energy in the sleeping soldiers—hidden energy—in the angles of their elbows and their knees, and their crisscrossed legs, in opposition on either side of the tomb, as their feet meet; and there is energy in the opposing reds, greens and blues of their clothes.

That heavy horizontal tomb speaks of a final repose, but there is energy there too, in its divisions, in the change of color from dark to light.

The browns and greens of the rectangular landscape swell, going up and down as if the earth itself were moving. And the rolling hills form an undulating horizon. The trees grow on either side of the rising man, and one feels earth and humanity are coming into being.

It is spring time, and as the critic Kenneth Clark points out, Piero shows that a contemporary humble Italian peasant and Christ can look and perhaps feel alike; than an early Italian spring morning of any year was like that year.

One of the great things I have learned from Eli Siegel is that there need be no split between what happens in art and what happens in life. “In reality,” he said, “opposites are one; art shows this.” When we are pleased by the bottles of Morandi as they are still and yet edgy, jumpy, even uncertain, and when we are pleased by walking, for instance, in a nice rhythm, with a little skip perhaps—the way children like to do—we are pleased by that oneness of energy and repose which is what reality made us to enjoy in the first place. What pleases us in Morandi, in Piero, in all art, is the oneness of opposites.

The way Christ stands, one foot raised, his arm at ease, has the composure every person wants—it is that oneness of vertical self and horizontal world which we saw as Morandi showed his bottles standing tall in a wide space, and which Mr. Siegel describes in Self and World.

But there is a relation of repose and energy which is beautiful and a relation which is not. Only Eli Siegel and Aesthetic Realism understand and described it.

I believe this explains why Piero della Franciesca has painted himself as one of the sleeping soldiers, one who did not awake to Christ's meaning.

Piero is asleep in a way none of the other soldiers are; one of them has covered his eyes with his hands because, it is said, he saw such glory and could not face it. Another soldier has his eyes averted. And the other rests with his spear as his pillow, slanting away from the serene figure.

But Piero is sound asleep. The repose of sleep has been called a little death in life and in that way it is like contempt or boredom. And Piero who wanted to see in such a large way, may have wanted to have a repose in his life he questioned himself about. Perhaps Piero saw in himself some of the sins Christ died for.

His clothing however, with its deep brown almost like the earth, is painted in such a way, we see there is a thinness between flesh and cloth, an activity in the brush strokes, which asks for awakening, for being affected.

I believe that Piero was wrestling in himself with the two aspects described in Eli Siegel's historic essay, “Art as Life.” These two sentences are central in our comprehension of the relation of artist and person. Mr. Siegel writes:

True indivuality is the repose arising from the relation of a self to all it has to do with. Bad individuality has in it a separation between outward action and a flat repose inwardly.

This portrait is a self-criticism. Piero, through the composition of art has changed the flat repose of separation into the simultaneous repose and energy which is in all accurate relation.

He places himself, un-helmeted, as individual, along however, with other soldiers, in front of the tomb, low in earth, supporting and leaning on, almost seeming part of, the pole which goes from the bottom to the top, from earth to the sky, in this painting.

The pole itself, like Christ and the trees, is a means of relation. And that banner, with its vertical symbol of self, and its horizontal symbol of world, is at rest and in motion in the air. It is still and waving as it touches the shoulder of Christ. It is a sweet victory of the oneness of opposites, painting in red and white.

Piero della Francesca died in 1492, just days before America was discovered. And the American philosophy founded by Eli Siegel and these Fifteen Questions, Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites?, see and comprehend him now, explain him now, and can teach every person what his art, and what all art, is for: to see opposites as one thing from the beginning of life to the end, and the beginning again.