SATIRE: MOCKERY AND COMPASSION AS ONE

IN HONORÉ DAUMIER AND DUANE HANSON

By Chaim Koppelman

from Four Essays on the Art of the Print

Aesthetic Realism and its critical principles have enabled me to see how two satirical works of art I have cared for—created more than a century apart—are beautiful, show respect for mankind and also can teach us how to be kinder people.

Aesthetic Realism describes the fight that goes on in every person between the hope to respect the world and people and the desire to have contempt—“the addition to self through the lessening of something else.” Contempt, including the way we are satirical and make fun of people different from ourselves in ordinary life, is what, intensified, causes the horrors of a Buchenwald, the ethnic warfare in Europe, and racism in our own country.

Satire as art is criticism that makes us laugh at what is contemptible in behalf of more respect. For contempt to be defeated this great principle stated by Eli Siegel must be studied: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

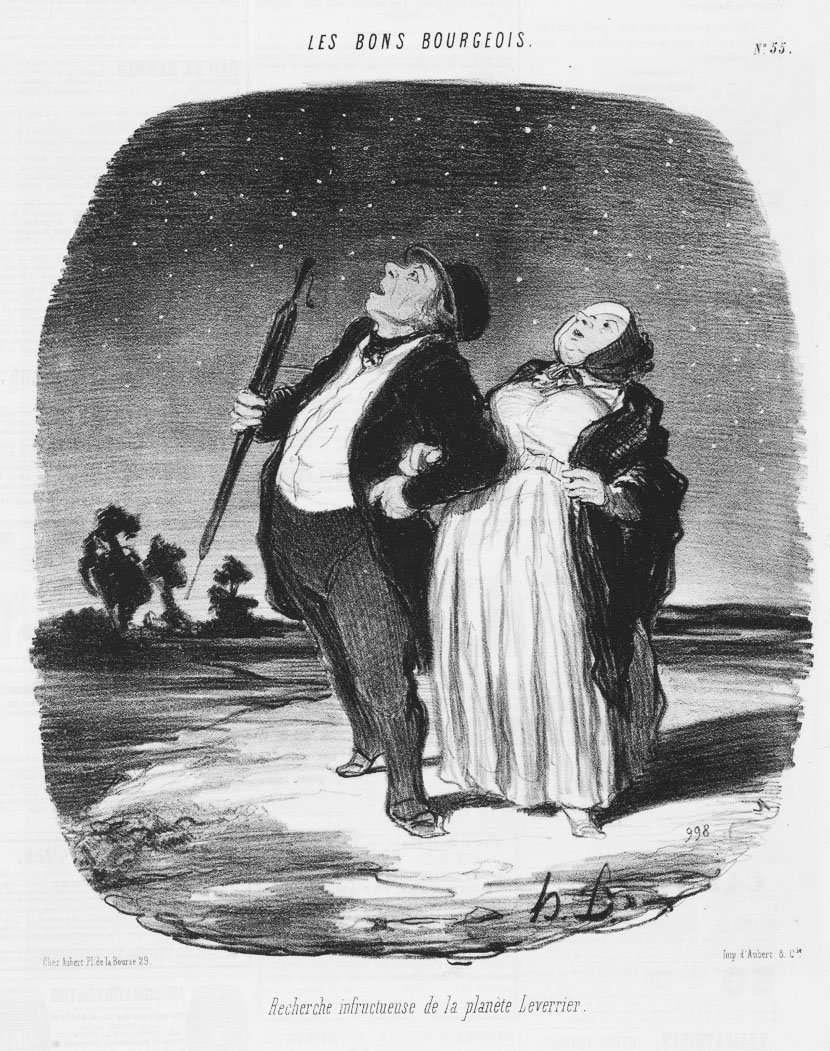

In two strikingly related works—a 19th century print and a 20th century sculpture, the artists looked at people one might easily have contempt for and instead had large respect. Honoré Daumier’s (1809-1879) lithograph, Fruitless Search for the Planet, dates from the great French artist’s “Pastorals” series of the mid-l840s in which he gently satirizes middle class Parisians on holiday trying to commune with nature. Tourists, by the American sculptor Duane Hanson, dates from 1970 and is now in the National Gallery at Edinburgh.

Honoré Daumier, Fruitless Search for the Planet, 1846. Lithograph

The aesthetic and ethical problem dealt with and resolved so memorably in both these works and in all good satire is described clearly by Eli Siegel:

Man wants to find deep meaning in the world; and he also wants to make fun. Man wishes to be kind, to honor the true meaning of pity; but he also wishes to sneer, to jeer, to have contempt, to have a wonderful, self-enhancing time through mockery. [He] has to ask how mockery and compassion have to do with each other.1

This is the only way we can like ourselves for how we see other people:

Humor can have good will in it. There is the jest that is imaginatively, aromatically benevolent. When man sees that his gift for contempt can go along with flexible justice and great kindness, man will at last think well of himself.... Satire and flowers will be in the same world.

Humor Can Have Good Will

“Mockery and compassion” and “satire and flowers” are made one so beautifully in Daumier. I think this is what Charles Baudelaire felt when he said, “His caricature is without bile or rancor...there is a foundation of honesty and good-naturedness.”

Daumier makes fun of our foibles with respect and great affection for mankind and its meaning. That is what made him beloved by the people of Paris and by this New Yorker more than a hundred years later.

We are all deeper than we know, and yet can sometimes appear not only awkward, but, like this couple, silly. The situation is ludicrous. A rather stout, elderly, middle-class couple, dressed for a stroll in the Champs-Elysees, stand in the middle of a deserted field at night, cozily arm in arm and looking up at the stars. The husband wears a black jacket and hat—and Daumier’s blacks have great depth—jauntily holding his umbrella at a sharp diagonal in the twilight evening sky. His plump wife wears a black wrap and her bonnet is tied demurely under her chin.

They Have Depth, Majesty, and Mystery

This print is beautiful because it is a oneness of opposites—the high and low, near and distant, heavy and light. Their forms begin with rather tiny feet, swell into rotundity and as they arch backwards with heads raised the forms taper again. As they look with wonder into the sky they have depth, majesty and mystery. Daumier has us look up at this couple, not condescendingly down. We laugh and are moved simultaneously. Daumier has evoked respect.

The couple is close and seen in relation to all space. Daumier relates the figures in the foreground to the tree shapes in the background. They stand in the spotlight and their shadows extend beyond them. They are dark and light like the world they are in. They are on their toes, their whole bodies lift, with heads raised, mouths open in wonder, looking up beyond themselves. This relation shown by Daumier of the depths of a person to a boundless universe is the way of seeing which is necessary for contempt to be defeated.

Aesthetic Realism has been crucial to my happiness and to my career as an artist. I have done many satirical prints and I had the honor of having my work discussed critically by Mr. Siegel in Aesthetic Realism classes. When I wasn’t sure whether I was having contempt or not in my work, Mr. Siegel asked me—and every artist should be asked this: “When you aren’t in your workshop, have you enjoyed too much making fun of people in your mind?”

Unfortunately, I had, and Mr. Siegel showed that contempt was making for technical difficulty in the engraving I was working on. He asked: “If you are satirizing are you regretful that you are?” I learned from Mr. Siegel and from how he himself was all the time what it means to put together beautifully compassion and criticism. I am very grateful to teach what I have learned to students in my printmaking classes at the School of Visual Arts, to distinguish between respect and contempt in an artist’s idea and technique.

The Tourists by Duane Hanson

I think that the unforgettable Tourists by Duane Hanson (1925-1996) is his best work because he was impelled by imaginative respect. Tourists is “benevolent,” even though at first these life-size painted and clothed figures seem to invite contempt. The sculptor saw reality’s opposites here—“satire and flowers” are made one. Decked out so tastelessly—he in his green Hawaiian shirt, tan checkered shorts, leather sandals, and actual camera paraphernalia, and she with her bright red stretch pants, her blue and white striped shirt, big beads, yellow hair net, big sun glasses, and finally, her patch worked, overstuffed beach bag—they too, like Daumier’s couple, look up in wonder into deep space.

Duane Hanson, Tourists, 1970. Polyester and Fiberglas.

I had a large art experience when I first came upon this couple exhibited at the Whitney Museum. My first response, like other museum visitors, was to laugh at this blatant display of bad taste. As we approached the two people however, saw their lovely expressions—he with his hand to his brow, both standing firm and looking up—tears came to people’s eyes. “Mockery and compassion” were one.

People have always wanted to see and to be seen with the good will that is art. That is what is taught by Aesthetic Realism: the art way of seeing the world, other people and ourselves as a co-presence of opposites.

REFERENCES:

1. Eli Siegel, The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, #127 (1975).

2. Ibid.

3. Charles Baudelaire, "Quelques caricaturistes français"; Complete Works of Charles Baudelaire, vol. II